There are a number of watch movements that are both chronograph-rated and moderately-priced. But perhaps none of these contemporary movements is as popular as the Valjoux 7750. First introduced in 1974, the 7750 was Valjoux’ answer to the Zenith El Primero automatic movement. Many watch enthusiasts have dismissed the 7750 as a cheap, generic movement. However, when properly tuned in, the 7750 meets COSC Chronometer standards, and is found in many quality watch brands, such as TAG Heuer.

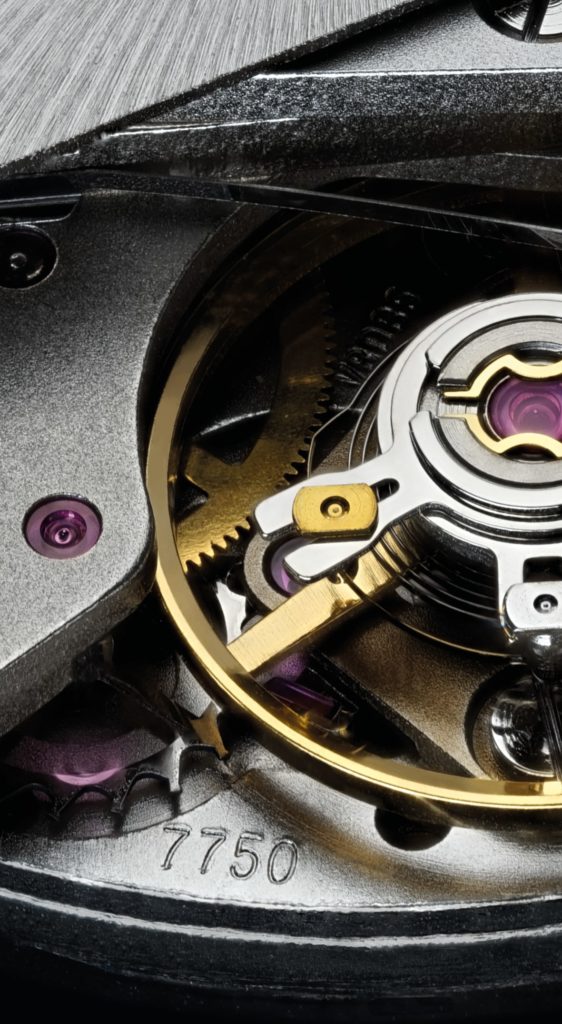

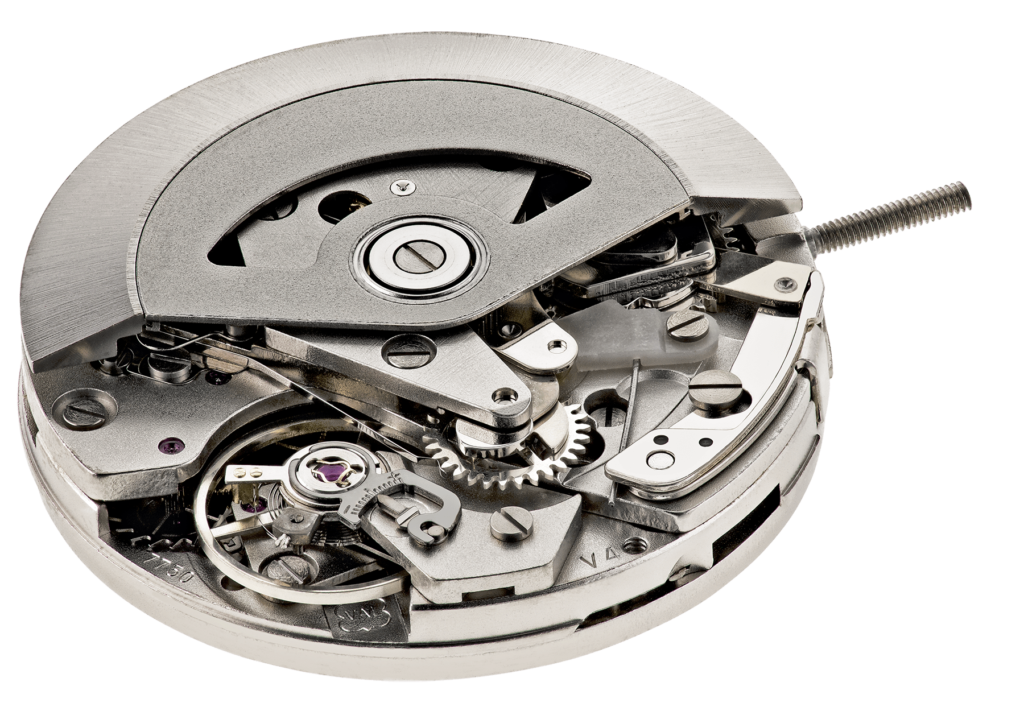

The 7750 has an automatic, self-winding module that’s attached to the top of the movement. It operates with a single double-click wheel, which winds in one direction. The 7750 measures 30mm in diameter, and is 7.9mm thick. The original version contained 17 jewels, while modern versions use 25.

The Valjoux 7750 takes a cue from many modern chronographs, with a heart piece limiter taking the place of the traditional column wheel. The heart piece limiter starts, stops, brakes, and resets the watch as needed. The modern version requires only two pushers for control, although the original coulisse-lever variants used three buttons. The heart piece lever also pivots, ensuring a highly accurate reset-to-zero function, both for the hour and minute hands. Earlier automatic movements did not have this feature, and were not 100 percent precise when resetting to zero.

The purpose of this design is to obtain similar accuracy while maintaining a lower price point. The levers and springs do not have to be manufactured to the same level of precision. There’s also more tolerance in the quality of the materials. This makes the coulisse-lever design objectively equivalent to an old-school column wheel, at a lower cost.

So, how did the Valjoux 7750 come to be? And why is it still so widely-used today? I’m about to walk you through the story of this classic movement, from its humble origins, to its early demise, to its resurrection in the 1980s, as well as modern developments.

The Origin of the 7750

Valjoux is a Swiss manufacturer that produces a variety of automatic watch movements. The word Valjoux is short for “Joux Valley”, which in turn is an abbreviation of “Vallée de Joux”, their original location. In addition to the 7750 movement, they’re also well-known for their chronograph ébauche movements. They’re currently a subsidiary of ETA, as well as a part of the Swatch Group.

But they began in the 19th century as an independent movement manufacturer. In 1931, they became a part of AUSAG, a conglomerate that bought up several independent Swiss movement manufacturers. AUSAG continued to grow throughout the decades, acquiring Certina, Oris, Longines, Eterna, and Edox, among others.

During the 1960s, there was intense competition among Swiss watchmakers to produce the latest and greatest automatic movement. With the end of World War II and Europe’s subsequent economic recovery, quality materials were available at lower prices than ever before. Moreover, the economic improvement meant that people were once again able to afford quality timepieces.

One particular movement, the Zenith-Movado El Primero, was released in 1969, and offered better performance than any automatic movement previously released. In addition to the El Primero, there was also the Chronomatic movement, also released in 1969 by a partnership between Dubois Dépraz, Buren, Breitling, Hamilton, and Heuer.

In addition, Japanese watchmakers were already releasing early quartz movements. Not only were these movements more accurate than traditional automatics, but they were also significantly cheaper, which put pressure on watchmakers who wanted to compete at a low price point.

This put AUSAG – and, by extension, Valjoux – in a bit of a pickle. All of a sudden, they were the weakest player in the game. To help them catch up, they hired a young watchmaker named Edmond Capt to develop a new movement. Their requirements were steep. They needed a movement that was chronograph-rated, reliable, and durable, and included a quick-set day and date. If that wasn’t enough, they also needed to develop this movement as quickly as possible.

In order to meet this speed requirement, Capt based his new movement on an older, hand-wound movement, the Valjoux Caliber 7733. Capt was also able to enlist the help of famed watchmaker Donald Rochat, as well as one of the first computer-aided design programs. This was one of the first times that a computer was used to aid in the development of a new automatic movement.

Capt’s main innovation was the new mechanism, a lever and oblong-shaped camp, which replaced older column wheels. As I already mentioned, this allowed for cheaper production, which would allow Valjoux to undercut their competitors on price. The result was a high-quality movement that stood out in comparison to the competition. It was fairly thick and wide compared to those competitors. However, it wasn’t just cheaper. It also had a unique rotor sound. It was also significantly lighter. Since it only wound in one direction, Valjoux could add a heavier oscillating weight, which could rotate faster in the non-winding direction. This provided a unique wrist feel, where the wearer can feel the movement wobble as it winds.

Capt succeeded in meeting his goals, producing the first Valjoux 7750 in 1973. Not only did it utilize 17 jewels, but it was also available in two frequencies: 21,600 BPH and 28,800 BPH. However, almost as soon as the 7750 hit the market, it seemed destined to die an early and ignominious death.

The Quartz Revolution

In its first year, the Valjoux 7750 sold an impressive 100,000 units, and seemed like a guaranteed hit with watchmakers and the public alike. But by 1975, the movement was on life support.

Similar to the El Primero, the 7750 was getting squeezed from both sides. On the one hand, elite, high-end watchmakers were capturing the luxury market. On the other hand, Japanese quartz movements were dominating the middle and lower end of the market. Simply put, there weren’t many customers willing to invest in a mid-priced automatic movement.

In 1975, Zenith-Movado discontinued the El Primero, citing low sales. Managers at Valjoux believed that there was no longer a market for the 7750, and they halted production. What’s more, they ordered all molds and dies to be destroyed as well. To his everlasting credit, Capt refused this second order. Instead, he put the molds, dies, and blueprints into storage, so they could be retrieved later if needed.

At first, Valjoux’ managers seemed to be correct. The drop in demand was so steep that it took until the 1980s to sell all remaining 7750 stock. However, in the early 80s, mechanical watches suddenly surged in popularity. Quartz watches, although accurate, were perceived as cheap, and people who wanted a fashion statement were giving automatic watches a second look.

Corporate Merger and Renewed Demand

During the late-1970s downturn, Swiss watchmakers did what many industries do in hard times: they consolidated. AUSAG and SSIH merged to form the Swatch Group. This new group now owned three different movement manufacturers: Valjoux, ETA, and Lemania. Lemania was considered “excess”, and was spun off as a separate company, Nouvelle Lemania.

This new company merged with Piaget, and bought Heuer in 1982. Heuer had previously been purchasing Valjoux’ remaining stock of 7750 movements. But Nouvelle Lemania did not want to buy movements from a competing company, and started using their own Lemania 5100 and LWO 283 movements in Heuer’s watches.

But in 1984, another watchmaker, Breitling, was in the market for a new movement. They were releasing a new version of the Chronomat to celebrate their company’s centennial anniversary. This watch, they decided, would be powered by the Valjoux 7750. This was a large, durable watch, and it had a truly innovative design. This design would restore Breitling to its status as a top-tier watchmaker, kicking off one of their most successful eras. And now, suddenly, Valjoux would need to start producing new 7750 movements, or they would lose their contract.

All of a sudden, Capt looked like a hero for saving the dies, molds, and blueprints for the 7750. Production immediately resumed. This second generation of the 7750 would be officially named the ETA/Valjoux 7750, although that was sometimes simply abbreviated to the ETA 7750. This new production would quickly become popular among other watchmakers, as well.

Watchmaker IWC also admired the 7750, and set about creating a watch that could take advantage of its features. Their technical director, Kurt Klaus, decided to use it as the basis for a new watch, the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar Chronograph. This watch would soon become iconic in its own right, and still fetches a generous price on the used market.

One interesting aspect of the Da Vinci is that Klaus refused to use computer aided design, although the technology was now widely available. Instead, he took a cue from his own mentor, previous IWC technical director Albert Pellaton. He designed the entire Da Vinci watch by hand, using a calculator to make all of his calculations. This old-school, hand-made design won the Da Vinci a lot of praise, and quickly make it a market leader.

Technological Renaissance

As the 80s ended and the 90s began, IWC continued to look for more ways to incorporate the 7750. To celebrate their 125th anniversary in 1993, they designed the Destriero Scafusia, which literally means the “Warhorse from Schaffhausen”. Schaffhausen is the Swiss town where IWC is headquartered.

The Destriero Scafusia has a perpetual calendar, a minute repeater, a flying tourbillon, and a split-seconds chronograph. With these extra components, the 7750 movement is partially obscured through the display case, although it’s still, for the most part, visible.

As the 7750 continued to gain popularity, it was used in more and more watches by several Swiss manufacturers. One of these manufacturers, Fortis, won a contract with Russia’s Roscosmos space program in 1994. They began issuing watches for the Russian cosmonauts on the International Space Station.

But the 7750 lacked one important feature: an alarm function. And Russian cosmonauts quickly began to complain about this absence. In order to meet these needs, Fortis hired Paul Gerber, an independent watchmaker, to design an alarm that would work with the 7750. The result was the first automatic watch to also feature an alarm.

Gerber also made their own modifications. They added a second spring barrel that powered the alarm, and modified the movement’s rotor to also power the spring barrel. This required an enlarged rotor, in order to add enough weight to wind both barrels. Gerber raised the rotor by a full 1.5mm to make room. This resulted in an entirely new movement, which Gerber called the F-2001. It was officially launched in 1998, and was updated again in 2012 in honor of Fortis’ centennial anniversary. This new version added a GMT function and a dual power reserve indicator, and has become a classic in its own right.

Another popular variant of the 7750 is Eterna’s 6036. This movement displays elapsed hours and elapsed minutes, allowing for an advanced timer function on the chronograph. It’s used in the Porsche Design Indicator P6910, which has jumping indicators at 3 o’clock, as well as a power meter.

Still Going Strong

As I write this, the 7750 has nearly reached its 47-year anniversary. And even at that age, the Valjoux 7750 is still one of the most popular automatic movements on the market. From its humble beginnings in 1973, it’s gone on to power some of the world’s most prestigious watches, as well as inspiring several variants that have become world-famous in their own right. Among the most prestigious 7750-based watches are Germany’s 1996 Watch of the Year, the Chronoswiss Opus. It’s also utilized in the Ikepod Megapode, Marc Newson’s most famous mechanical watch.

Is the 7750 an advanced piece of engineering? In terms of today’s technology, no. But it’s a sturdy workhorse that, for lack of a better term, keeps on ticking. Some watch aficionados dismiss it as lowbrow. In my opinion, and based on its history, it’s anything but.

Sources: Information and images from this article were sourced directly from ETA SA, Manufacture Horlogère Suisse. I reached out to them personally. Official website: https://www.eta.ch/

Hi! I found this very interesting. I have an Altanus Chronograph watch I bought from an eBay seller who really didn’t know much about the watch he was selling, didn’t even have a photo of the movement, but the gentleman had 100% feedback so I went ahead and purchased the watch only to find when taking the back off it was a 17 jewel version of the 7750 movement. The watch looks like it needs a good clean and a service which it will have, but keeps very good time and all the functions work perfectly. I noticed that the rotor on my Altanus was exactly the same as the one in your article. I wonder if you could tell me anymore about the movement I have i.e. approximate year of manufacture. I would like to send you the photo of my movement but not sure I can attach it here.

Thanks for stopping by, I can certainly have a look for you. Please send me an email through our contact us page.

I am looking at purchasing a watch on eBay listed as an Alexander 25 jewel Valjoux 7750. Is there any way you could verify the watch based on the sellers ad alone?

Hi Matthew,

I would like to ask you if the Valjoux movements used in 80s Breitlings (17 Jewels Chronomats and Old Navitimers) were built in 1973-1975 or during the resurrection of 7750 in 1985 and later? It seems that they used old stocks from 70s. Am I right?

Great and informative article Matthew. Thank you for writing it.

ETA/Valjoux 7750 is definitely a great movement in my opinion.

I started using it in my Chronograph line in 2007 and I still do.

Unidirectional wind, but still one of my favorite movements.

It is definitely a workhorse.